the Hall of Miller and Eric

Dan Brouthers

HoME 2.0, Elections of 1901 and 1906

It was almost eight years ago now that we held out first election at the Hall of Miller and Eric. It was an extremely nerve-wracking time even though we had essentially zero readers then. In fact, our first 1901 election post hasn’t even been viewed ten times. In other words, the nervousness didn’t originate from putting ourselves out there.iIt occurred because we presented ourselves with a daunting imaginary responsibility, and we just wanted to get it right.

1901 Election 2.0

Back in 2013, we elected only three players in the 1901 election, Jack Glasscock, John Clarkson, and Deacon White. Those were the only three Miller supported during the first go ‘round. Eric added George Wright, King Kelly, Paul Hines, Ross Barnes, and Charlie Bennett. Clearly Eric was more confident in his rankings, a pattern we begin to see again this election. So who gets in this time? To get a plaque, a player needs a vote from both of us. Here are the 2.0 results.

Miller Eric 1 John Clarkson Tim Keefe 2 Jack Glasscock John Clarkson 3 Old Hoss Radbourn Jack Glasscock 4 Tim Keefe Deacon White 5 George Wright Charlie Bennett 6 Old Hoss Radbourn 7 George Wright

That means we elect five, each of the five Miller supported. But what about Deacon White? He made it eight years ago as one of only three players Miller supported. There’s no story here. It’s just patience. White’s fans shouldn’t worry. Not yet.

We’ve now elected five of the 264 players who will eventually form the updated Hall of Miller and Eric.

1906 Election 2.0

Miller remained extremely conservative with his second ever vote, supporting only Eric’s first three choices: Cap Anson, Roger Connor, and Dan Brouthers. Eric showed that he was further along in the process once again, voting for the three first basemen plus Buck Ewing, George Wright (again), King Kelly, Paul Hines, Ross Barnes, and Charlie Bennett (again).

The second time around, our ballots showed two people who have been working on this together for a great deal of time. Sometimes we fear groupthink, and that’s something about which we should always be aware. However, we’re both such independent thinkers that we believe, correctly or not, that our similar results are more likely the result of logical decision-making than remaining inside a bubble of two. So without further ado, here’s how we voted in 1906.

Miller Eric 1 Cap Anson Cap Anson 2 Buck Ewing Roger Connor 3 Roger Connor Dan Brouthers 4 Dan Brouthers Buck Ewing 5 Amos Rusie Amos Rusie 6 Charlie Bennett Deacon White 7 Charlie Bennett

Once again, each of the six players Miller supported are now in the HoME. And Charlie Bennett becomes the first player elected on a ballot other than the first. At this stage, only Deacon White has received a vote from either of us and is not in the HoME.

After two elections we’ve elected eleven of our eventual 264. That compares to just six during our first series of elections.

A week from today, we’ll share the results of our 1911 and 1916 elections. Maybe Miller gives a vote to Deacon White? Maybe Eric offers a shorter ballot than Miller, something that didn’t happen until our first 1979 election? We shall see.

The Best 125 First Basemen Ever

Joey Votto might be the coolest player in baseball. That’s one of the reasons I’ve spent a bit of time the last couple of years wishing his career has just a little different shape. See, Eric looks at him as the 16th best first baseman ever, while I have him at 23rd. He’s already in for Eric and certain to get there for me. Unfortunately, he’s only hit 30 homers twice, only driven in 100 runs three times, is below 2,000 hits, and is below 1,000 runs and runs batted in. In other words, there’s a shot the BBWAA could find a way not to support him. Here’s hoping two years from now those career totals are all on the more hopeful side. Votto has had an amazing career and will absolutely deserve induction.

Today we’ll examine Votto and the best 125 players ever to play first base. As you might expect, first base is home to our most disagreements regarding position. Please remember that Eric places a player where he was most valuable, while I place him where he played the most games. And lots of players move to first base when they’re less able to occupy a more meaningful place on the defensive spectrum. So as you might expect, first base is home to our most disagreements regarding position. I include Pete Rose, Rod Carew, Ernie Banks, Dick Allen, Pedro Guerrero, Darin Erstad, Mike Napoli, and Jeff Conine here. For Eric, those guys are placed all over the diamond. Rose and Conine are left fielders, Carew belongs at second base, Allen and Guerrero are third basemen, Banks is a shortstop, Erstad is a center fielder, and Napoli is a catcher.

Check out those catchers if you missed them, and make sure you check back for other positions. Without further ado, our top-125 first basemen of all time.

Second base is coming up on Monday. Please join us then.

Miller

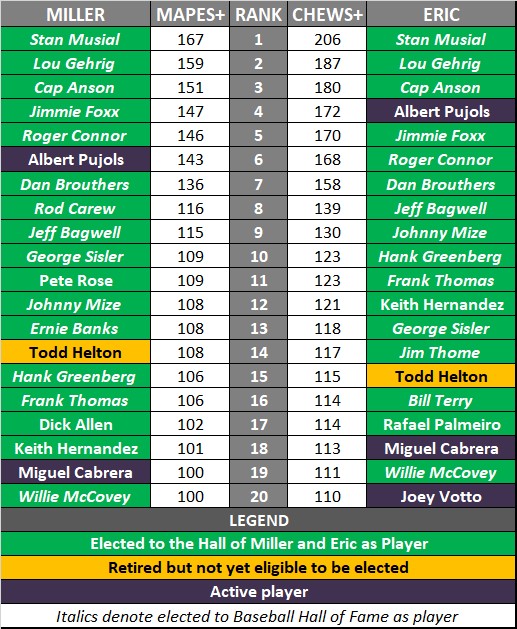

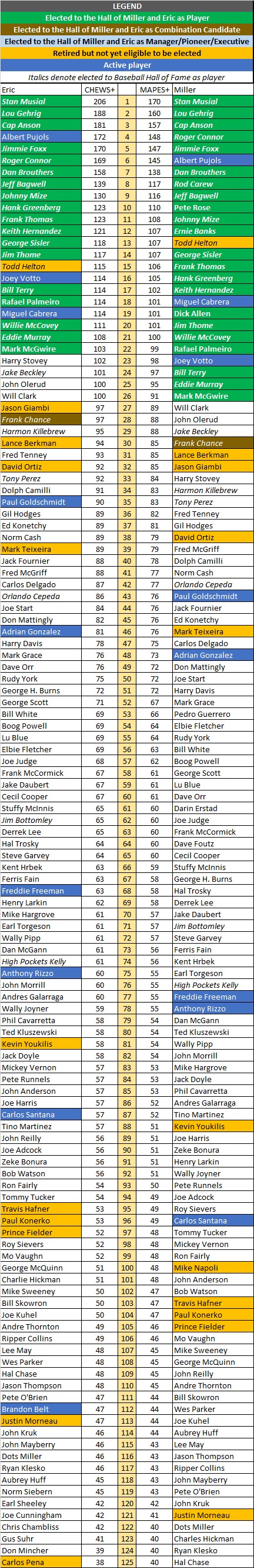

All-Time HoME Leaders, First Base – 1-20

It’s hard to believe that the Hall of Miller and Eric has been around for nearly five years now. As transparently as we can, we’ve tried to determine the players, managers, executives, and pioneers who should rightfully be enshrined in Cooperstown. Also, we’ve tried to respond to what our readers have requested. With both transparency and commitment to our readers in mind, today we embark on the start of a 22-week journey where we reveal the top-40 players at every position based on Eric’s CHEWS+ (CHalek’s Equivalent WAR System) and my MAPES+ (Miller’s Awesome Player Evaluation System).

Each Monday until we finish the tour around our rankings, we’ll reveal half of a position’s top-40. As for pitchers, we’ll go 120 deep. Along the way, we’ll work on finding a place to store the information so you have quick access to it – and so you can see how our rankings compare to yours. So let’s get started!

First Base – The Top-20 All-Time

Where do we project the active players to finish in our rankings?

Albert Pujols

Pujols is no longer a good player, and he’ll be 38 this year. The only way he moves from 7th on the list is when I change my evaluation system. –Miller

I project him speaking at a podium in Cooperstown about eight to ten years from now.—Eric

Miguel Cabrera

A lot depends on how done one thinks he is. Even if he can still play better than 2017, he’s at an age where a regression won’t be toward his career-average productivity, but to a rate somewhere between there and 2017. Maybe he’s got a couple three-WAR years left in him? Either way, he’s a HoMEr, it’s only really a question of whether he’s #20 or #16—Eric

I choose to be positive here. Miggy is “only” 35, and he was an excellent hitter as recently as 2016. He could pass two or three more guys, and that’s the optimistic point of view. –Miller

Joey Votto

It’s kind of hard to say, actually. Votto is a very uncommon player type when you start to drill down into his profile. The reason he’s uncommon is that he’s far less athletic than other super productive hitters of his caliber. So I drew up a list using the BBREF Play Index (subscribe today! It’s cheap and amazing!). Critera: Ages any through 33, with baserunnning runs less than 0, sorted by batting runs. Votto has 428 batting runs, and here’s everyone above 350:

- Miguel Cabrera: 581 Rbat in 9000 PA

- Frank Thomas: 565 Rbat in 6878 PA

- Manny Ramirez: 499 Rbat in 7225 PA

- Jim Thome: 452 Rbat in 7039 PA

- Joey Votto: 428 Rbat in 6141 PA

- Gary Sheffield: 415 Rbat in 7357 PA

- Todd Helton: 404 Rbat in 6758 PA

- Reggie Jackson: 394 Rbat in 7340 PA

- Wade Boggs: 393 Rbat in 6725 PA

- Mike Piazza: 388 Rbat in 5734 PA

- Willile McCovey: 373 Rbat in 5734 PA

- Lance Berkman: 371 Rbat in 6355 PA

- Harmon Killebrew: 359 Rbat in 5525 PA

- Mark McGwire: 358 Rbat in 5633PA

- Eddie Murray: 357 Rbat in 8480 PA

- Jason Giambi: 354 Rbat in 5784 PA

Before we talk about what happened after age 33, a note that on a per-PA basis, the only hitter on this list who outperformed Votto is the great Frank Thomas.

Next I plotted out what each of these guys did after age 34 and compared the group’s aggregate performance at each age to their overall performance through age 33. Then I used the age-by-age comparisons to project Votto through age 40 with simple math based on his career total through age 33. That added up to 550 batting runs for Votto. I wanted to account for those players whose careers ended before age 40, and for those seasons, I used Excel’s trend function to provide Rbat estimates for missing seasons, which, as you might surmise, weren’t very flattering in most cases. Even doing so, I got to 530 Rbat for Votto. So a range of 530–550 runs.

I ran a PI search in the expansion era to see how many players have cleared 500 Rbat. It’s just 16 total. Albert Pujols and Miguel Cabrera are the only active players on the list. Alex Rodriguez is on the list but not yet eligible to be voted on by the Hall of Fame or the Hall of Miller and Eric. Here’s the list of every currently eligible player that the Hall of Fame hasn’t elected who exceeded 500 Rbat for their careers: Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Edgar Martinez. Two steroid guys and a DH who will be elected in 2018. We’ve elected all 14 eligible players so far. Heck, the only eligible players we haven’t elected among the 23 with 400+ Rbat thus far are Vlad Guerrero, Willie Stargell, Harmon Killebrew. Vlad has already drawn my vote, and he may get Miller’s someday soon as well. Jason Giambi and Lance Berkman are probably below the in/out line for us too, but they haven’t had to run the gauntlet yet. None of them is as good a hitter as Joey Votto.

Votto has, in my opinion, already done enough to get my vote. As long as the rest of his career progresses pretty normally, he’ll start climbing the ladder at his position and surprise a lot of people with how high he could finish.—Eric

Where do our rankings diverge the most from the conventional wisdom?

I’m proud to say it’s Keith Hernandez. He belongs in the Hall, and it’s not a particularly close call. Oh, and voters next winter will show us by just how much we eschew conventional wisdom when 26 of them vote for Todd Helton. –Miller

For me, it’s clearly Keith Hernandez. A lot of people have talked him up, but I’m probably his best friend on the internet. I probably place more emphasis on fielding at first base than most observers. But Hernandez is the Ozzie Smith of first basemen with a good enough bat. Also, my 1985 Topps All-Star card informs me that he’s a leader in Game-Winning RBIs.—Eric

Where do we disagree with one another the most?

We basically don’t disagree at first base at all. The rankings are a bit different, but all are within anyone’s comfort level for margin of error. The thing we disagree on most as far as first base is concerned is selecting the guys who fit the position. I put Ernie Banks, Pete Rose, Rod Carew, and Dick Allen here, while Eric sees them as a shortstop, a left fielder, a second baseman, and third baseman, respectively. I place guys at the position they played most, while Eric prefers to place them where they accumulated the most value.—Miller

Ernie Banks is a good example that demonstrates why each of our positions makes sense. Miller says the place where a fellow played the most is his primary position, which makes a lot of sense. I look at the fact that Banks accumulated roughly 35 Wins Above Average and 54.7 Wins Above Replacement at shortstop, then added -1.5 WAA and 10 WAR at first base, and I think he’s a shortstop. Actually, I use my own adjusted WAA/WAR totals when I’m assigning positions, but in this case, it doesn’t matter much. But it’s not always cut-and-dried for me. Rod Carew is within tenths of a win, and I could put him at either first or second base. I chose to stay consistent and place him where he accrued the most value, second base.—Eric

Are there any players that MAPES+/CHEWS+ might overrate or underrate?

Frank Thomas played more than half his games at DH. For the purposes of ranking players, we’ve chosen to place majority DHes at the position they fielded the most. Someday when there are enough DHes in the HoME to split them back out, we may find that Thomas (and Edgar Martinez at third base) are a little better or a little worse in our rankings when they are only compared to designated hitters. For now, it’s good enough. —Eric

I sometimes wonder if three of the seven best first basemen ever really could have played before the turn of the last century. Though I suspect they didn’t, I just don’t have a better way. —Miller

The HoME 100: #50–41

As the countdown rolls on, we move into the top fifty. Check out the rest of of our list here: #100–91, #90–81, #80–71, #70–61, and #60-51

#50-41

50. Wade Boggs (ESPN Rank: 73)

MILLER: When there’s a recent guy who ESPN ranks low, you know his career wasn’t understood by the mainstream. The best four hitters ever without a nine-WAR season according to my numbers are Boggs, Mel Ott, Eddie Mathews, and Al Kaline.

49. Gary Carter (ESPN Rank: NR)

MILLER: I feel badly for Carter. He’s historically underrated, largely because he played the same position at the same time as an inner circle guy. This is the same problem Tim Raines has with Rickey Henderson. It’s the problem Alan Trammell has with Cal Ripken. It’s part of the problem Jim Edmonds has with Ken Griffey. And it’s even part of the problem Eddie Collins has with Rogers Hornsby. At least Collins and Carter are in the Hall.

48. Bert Blyleven (ESPN Rank: NR)

ERIC: Man, ESPN really has something against those 1970s 270+ winners. Of course, Rik Albert didn’t win 300, but close enough. What do you have to do to get on a list at ESPN? Bly threw 60 shutouts, which is more than all but 8 men in MLB history. Three of those guys (Spahn, Ryan, and Seaver) threw only 2, 1, and 1 more goose eggs respectively. OK, well, maybe shutouts isn’t your thing. How about strikeouts? Blyleven is fifth all time. I thought Bill James was foolish about a decade ago to write that Blyleven probably didn’t deserve the Hall. I think ESPN was foolish to forget him on this list.

47. George Brett (ESPN Rank: 32)

ERIC: One of the least researched aspects of baseball right now is coaching. George Brett credits Charlie Lau with remaking his approach at the plate and turning him into a Hall of Fame batsman. Baseball players exist in a meritocratic, performance-centric industry. Your performance is on the back of your baseball card, and anyone can see how well you’re doing. Think about the kind of ego you have to have to succeed in the big leagues. You’ll fail more often than not. You’ll face the constant pressure of someone else waiting to take your job. You’re one injury away from oblivion. You got to have a strong ego, and it seems as though baseball mostly weeds out the weak-egoed before they reach MLB. So when a player, therefore, tells the world that he owes his career to a coach, that’s really saying something. He’s giving credit to someone else, when sports in our country is all about the rugged man succeeding in moments of great pressure. Particularly in a game like baseball where nearly every play involves discreet moments of individual execution. We have to pay attention to what George Brett says here. Coaching is a place where the field of sabrmetrics could be doing a lot more work.

46. Dan Brouthers (ESPN Rank: NR)

ERIC: Brouthers is to Roger Connor as Jimmie Foxx is to Lou Gehrig. Exact contemporaries at the same position who dominated the league for years. The comparison takes you only so far because the gap between Gehrig and Foxx is good bit wider than that between Brouthers and Connor. Well, and Cap Anson was around in the 1880s and 1890s too and doesn’t have an analog for Gehrig and Foxx (Greenberg came too late). But you get the idea.

45. Eddie Mathews (ESPN Rank: 56)

ERIC: It seems like Mathews has lost some star power of the years. He’s something of a forgotten great. Look back at his statistical record. It’s really, truly impressive. It also underscores how badly the Braves of the late 1950s and early 1960s undershot the mark. After appearing in the 1957 and 1958 World Series, they fumbled away the 1959 pennant and then settled in as mere contenders. This team, however, was absolutely loaded with core talent. GMs dream of a core of Aaron, Mathews, and Spahn to build around. Add in Lew Burdette, Johnny Logan, and Joe Adcock as contributors, and a couple years later Joe Torre comes along then Phil Niekro. Wow. But after GM John Quinn’s departure to Philadelphia following the 1958 season, the Braves’ leadership faltered and with it Milwaukee’s golden era of baseball. One wonders if we’d be talking about the Atlanta Brewers today had the Braves followed on with more pennants.

44. Phil Niekro (ESPN Rank: NR)

MILLER: The anti-knuckler bias is real. I’m guilty myself. I’ve allowed Red Sox All-Star Steven Wright to languish on my fantasy baseball bench, and ESPN refuses to put one of the fifteen best pitchers ever on their list.

ERIC: And if the knuckler were easy to throw, the big leagues would be filled with 40-year-olds on long-term deals.

43. Joe Morgan (ESPN Rank: 38)

ERIC: Oh, how I miss Fire Joe Morgan. But we’re here to praise Little Joe, not to bury him. As has been pointed out many times, despite his inability and unwillingness to understand sabrmetric principles, Morgan represents something of an archetype for them. He didn’t hit for a high average, instead he walked all the time and hit for surprising power. On the bases he rarely made mistakes and his SB% is one of the highest on record. Plus he represented an important sabrmetric idea: the defensive spectrum and the value of position. He wasn’t quite average afield, but he wasn’t a Jeteresque sinkhole with the glove either, so Morgan stuck at second. Compare to someone with a very similar game: Tim Raines. Both were remarkable percentage players. Raines, in fact, came up as a second baseman, and had he been able to remain there would likely have been Morgan-lite. Raines wasn’t quite as good a player as Morgan overall, he mostly lacked Joe’s power, but the biggest and most stubborn gap in their value is the positional adjustment. Raines loses 86 runs as a leftfielder, and Morgan picks up 73. That’s a 140 run gap, or 16 wins. Give Raines 16 more wins, and he ends up at 85 WAR against Morgan’s 100. All of which is to say that position really does mean a lot and the effect it has on our perceptions of players and the value they bring is very important.

42. Carl Yastrzemski (ESPN Rank: 53)

Yaz is one of only eleven hitters with a pair of 10 WAR seasons. The only two to reach that height since Yaz are Barry Bonds and Cal Ripken.

41. Pedro Martinez (ESPN Rank: 11)

Pedro only pitched 200 innings seven times. He only won 15 games six times. The wins don’t matter, but the innings explain why a pitcher who has a claim to the best peak in history only having seven years of 6+ WAR. But how about that 2000 season? He allowed more than three runs only twice, and he allowed one or zero seventeen times.

THE WORLDWIDE LEADER IN SPORTS’ 50–41

Nolan Ryan

Mariano Rivera

Lefty Grove

Cal Ripken

Ernie Banks

Bob Feller

Satchel Paige

Steve Carlton

Yogi Berra

Tris Speaker

MILLER: I think Ernie Banks is probably the most overrated player on ESPN’s list. While he averaged almost 8 WAR per year in the six years before he hurt his knee in 1961, he was a pretty ordinary thereafter, averaging less than 1.3 WAR per year for the last decade of his career. We remember him as an elite level shortstop, and indeed he was that. We don’t tend to think of him as an ordinary first baseman, but he was that too.

In Support of Sal Bando

In my attempt to justify supporting Athletic and Brewer third baseman Sal Bando, I noticed that he totaled more WAR from 1969-1973 than any player in the game. Clearly, Bando isn’t in the Hall of Fame, nor is in the Hall of Miller and Eric. So I got to wondering, how many other players led the game in WAR over five years and aren’t in the Hall or HoME? So that’s what we’re going to look at today. Who was the game’s best non-pitcher by WAR from 1871-1875, from 1872-1876, from 1873-1877… You get the point. Right?

1871-1875, 1872-1876, 1873-1877

Ross Barnes was the dominant player in the earliest days of the majors, leading our troops through the game’s first three five-year runs. While Barnes isn’t in the Hall, he reached the HoME on his sixth ballot in 1926.

1874-1878, 1875-1879

Deacon White took over for the next two periods, starting in 1874 and ending in 1879. The star third sacker had to wait until 2013 to make it to the Hall, but he got into the HoME in our very first election in 1901.

1876-1880, 1877-1881, 1878-1882, 1879-1883

The next four periods belonged to Cap Anson. The first player ever with 3000 hits reached the Hall in 1939 and the HoME the first time he was eligible in 1906.

1880-1884

Who’s Fred Dunlap, and what’s he doing on this list? Sure Shop was a second baseman who played for parts of a dozen seasons, though only ten full seasons. He got a ton of his value, as did a lot of players, from the 1884 Union Association, a failed “major” league that only existed in 1884. Twelve teams participated, only eight of which topped 25 games. Dunlap earned a translated 7.4 WAR that season for a St. Louis Maroons team that went 94-19. He won the triple slash triple crown and also led the league in hits, runs, and homers. The 1936 the Veterans Committee supported him with 2.5 votes (don’t ask), while we wrote his obituary after his fifth election in 1921.

1881-1885, 1882-1886, 1883-1887

Dan Brouthers won our next three games. He reached the Hall of Fame in 1945 and the HoME on his first ballot in 1906.

1884-1888, 1885-1889, 1886-1890, 1887-1891, 1888-1892

Roger Connor finished the ABC 1B who dominated the early days of the game with five wins. Like Anson and Brouthers, he reached the Hall in his inaugural 1906 campaign. And he joined his mates in the Hall in 1976.

1889-1893

Not so fast, Dan Brouthers is back for one more run.

1890-1894, 1891-1895

Sliding Billy Hamilton with his great speed and strike zone control took our next two periods. The Hall honored him in 1961. The HoME did the same his first time around in 1911.

1892-1896, 1893-1897

The next two periods go to Ed Delahanty, who swept away the game before being swept over Niagara Falls to his death in 1903. The Hall elected Big Ed in 1945. We did the same when he was first on our ballot in 1911.

1894-1898

Hughie Jennings becomes the first guy to take the title just once and still make it into the Hall. Ee-Yah got to Cooperstown in 1945. But he never made it to the Hall of Miller and Eric, as we considered his case 35 times before writing his obituary in 1997. The problem for Jennings, we think, is that he had four incredible seasons, one other very strong one, and nothing else. He becomes the second non-HoMEr to dominate his league over a five-year period.

1895-1899, 1896-1900, 1897-1901, 1898-1902

Ed Delahanty returns with four more titles. Jennings interrupted Big Ed’s run with a very short period of greatness.

1899-1903, 1900-1904, 1901-1905, 1902-1906, 1903-1907, 1904-1908, 1905-1909, 1906-1910

Based on this run of eight straight periods, it might seem that Honus Wagner was the game’s greatest player to this point in history. I can buy that. The Flying Dutchman was a member of the Hall’s inaugural 1936 class and made it into the HoME when he hit our ballot in 1926.

1907-1911, 1908-1912, 1909-1913

You might have thought Ty Cobb would have a longer run atop the game than three periods. He got the most votes in the Hall’s first vote in 1936. And that’s the same year he reached the HoME on his first ballot.

1910-1914, 1911-1915

Might Eddie Collins and his two titles rank as the game’s most underrated inner circle guy? And is that even a distinction? In 1939 he made it to the Hall. In 1936 he made it to the HoME on his first try.

1912-1916

Tris Speaker took the honors for just one five-year run. But the Grey Eagle made it to Cooperstown in 1937 and the HoME in his first try in 1936.

1913-1917, 1914-1918, 1915-1919

I knew it didn’t make sense that Ty Cobb led for just three periods. Here are three more.

1916-1920, 1917-1921, 1918-1922, 1919-1923, 1920-1924

Lemme tell ya, sports fans, about a guy named Babe Ruth and his five periods atop the list. He was an original Hall member, finishing second to Cobb in 1936. And he became a HoMEr in 1941.

1921-1925

It’s nice that Rogers Hornsby could get his place in the sun. Were it not for this little blip, the 1942 Hall of Famer and first-ballot 1941 HoMEr might be the best player never to take the five-year title.

1922-1926, 1923-1927, 1924-1928, 1925-1929, 1926-1930, 1927-1931, 1928-1932, 1929-1933

Surprising nobody, Babe Ruth is back for eight more. That’s thirteen titles. Our reigning champ.

1930-1934, 1931-1935, 1932-1936, 1933-1937, 1934-1938

I’m a bit surprised that the run at the top, five wins, lasted as long as it did for Lou Gehrig. The Iron Horse reached the Hall after a 1939 special election. His election to the HoME, on his first ballot, in 1946, was equally special.

1935-1939, 1936-1940

The baseball player most likely to show up in your crossword puzzle, Mel Ott, is next. The Hall honored him in 1951. We did the same the first time we could in 1956.

1937-1941, 1938-1942

Mr. Coffee, Marilyn Monroe, and this! Joe DiMaggio checks in next with his two titles. The Yankee Clipper became a Hall of Famer in 1955. The HoME erected his plaque in 1961, the first time he was eligible.

1939-1943

One and done for Teddy Ballgame? Ted Williams reached active duty status in the navy, missed the 1943 season, and still led over this period. He became a Hall of Famer in 1966 and a HoMEr on his first crack that same year.

1940-1944, 1941-1945

Even during WWII, our winner makes sense. Lou Boudreau was the game’s best player for two periods. He reached Cooperstown in 1970. And like so many others on this list, he was a first ballot HoMEr in 1961.

1942-1946, 1943-1947

Did you know that Stan Musial led the NL in triples five times? Now he has two more titles. The Hall elected him in 1969. The HoME did so when he first became eligible in 1971.

1944-1948

Old Shufflefoot, Lou Boudreau, is back.

1945-1949, 1946-1950

And Ted Williams is back from the war and back on top two more times.

1947-1951, 1948-1952

At least until Stan Musial took the title back with two more.

1949-1953

Jackie Robinson took the game by storm and quickly became one of its greats. Cooperstown acknowledged him in 1962. We did the same on his first ballot in 1966.

1950-1954, 1951-1955

How great is this? Stan Musial is back for a third pair of titles, making him the only player ever to retake the title two times after losing it.

1952-1956, 1953-1957, 1954-1958, 1955-1959, 1956-1960

I’m a little surprised Mickey Mantle’s run was quite as long as his five periods considering the competition at the time. The Hall welcomed the Commerce Comet in 1974. The HoME did so as soon as we could in 1976.

1957-1961, 1958-1962, 1959-1963, 1960-1964, 1961-1965, 1962-1966, 1963-1967, 1964-1968

Yeah, Hank Aaron is the best player ever to never top this list, I’d say. This run of eight belongs to Willie Mays. The Hall said “Hey” in 1979. And on his first ballot, we did the same thing that same year.

1965-1969

No run for Aaron, but one for Roberto Clemente? Okay. A special election sent Clemente to upstate New York in 1973 just three months after his death took him to upstate heaven. Clemente was a first ballot HoMEr in 1978.

1966-1970, 1967-1971

Carl Yastrzemski, buoyed by his triple crown season of 1967, gets two periods on this list. We welcomed him on the first ballot the same year the Hall did, 1989.

1968-1972

Roberto Clemente is back for one more go.

1969-1973

Finally, here’s the reason I’m writing this post. Sal Bando was baseball’s best non-pitcher by WAR for a five-year stretch. He becomes only the third player ever with that distinction who’s not in the HoME. The first two, as you’ll recall, were Fred Dunalp and Hughie Jennings. Both have a fatal flaw. Dunlap has a lot of his value tied up in a dubious 1884 campaign, which is how he got to the five-year top in the first place. And Jennings only has five good years, albeit four great ones, which is how he got on this list. Bando is different. He led the game for five seasons, yet he also posted two All-Star-level seasons and three others of 3+ WAR outside of that stretch. Bando is indeed a strange player by that account. The combination of his uniqueness in this regard, an underpopulated era, and an underpopulated position give me confidence that my continued support of Bando is wise.

1970-1974, 1971-1975, 1972-1976, 1973-1977

Joe Morgan was a little guy who packed a big punch and won four titles. Cooperstown welcomed Little Joe in 1990. We did the same. It was his first ballot.

1974-1978, 1975-1979, 1976-1980, 1977-1981, 1978-1982, 1979-1983, 1980-1984

Eight home run titles and outstanding defense helped to make Mike Schmidt the best in the game seven times. He reached the Hall and the HoME as soon as he could, in 1995.

1981-1985, 1982-1986

Rickey Henderson did it with speed, defense, pop, and plate discipline for these two periods and nearly his whole career. Cooperstown elected him in 2009. I would expect the HoME to follow suit that year.

1983-1987, 1984-1988, 1985-1989, 1986-1990

Wade Boggs was an on base machine. With four periods of dominance, getting into the Hall in 2005 was no surprise. A couple of elections from now I fully expect he’ll make it to the HoME.

1987-1991, 1988-1992, 1989-1993, 1990-1994, 1991-1995, 1992-1996, 1993-1997, 1994-1998, 1995-1999

Long list, huh. Nine periods. It’s Barry Bonds. Even if the Hall never welcomes him, the HoME will in 2013.

1996-2000

Another guy who has Hall of fame troubles, Alex Rodriguez, breaks Bonds’ streak. We’ll see in a few weeks if he has anything left.

1997-2001, 1998-2002, 1999-2003, 2000-2004, 2001-2005

It’s Barry Bonds again. These five titles give him a record 14 in all. Yeah, he was this good.

2002-2006, 2003-2007, 2004-2008, 2005-2009, 2006-2010, 2007-2011, 2008-2012

Albert Pujols might not be the beast he once was, but he’s still averaging 3.5 WAR per year on the west coast.

2009-2013, 2010-2014

If you’re wondering whether or not Robinson Cano will get into the Hall of Fame, the comparison to the above players would seem to be in order. Every other player with at least two such titles is either in the Hall, going, or named Bonds.

Conclusions

There have been 35 players to lead baseball in non-pitcher WAR in history. Of those, 25 made it into the Hall of Miller and Eric on their first ballot: Deacon White, Cap Anson, Dan Brouthers, Roger Connor, Billy Hamilton, Ed Delahanty, Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Tris Speaker, Babe Ruth, Rogers Hornsby, Lou Gehrig, Mel Ott, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Lou Boudreau, Stan Musial, Jackie Robinson, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente, Carl Yastrzemski, Joe Morgan, Mike Schmidt.

Three others will get there as soon as they’re eligible: Rickey Henderson, Wade Boggs, Barry Bonds.

Three more are still active: Alex Rodriguez, Albert Pujols, Robinson Cano.

One player, Ross Barnes, took six ballots. But to be clear, Barnes should have gotten into the HoME in 1901. Eric voted for him, but I was being very patient and overly cautious.

There are only three players remaining.

- Fred Dunlap played ten full seasons and dominated the very weak Union Association in 1884.

- Hughie Jennings played twelve full seasons, though he only played 100 games in seven of them. Only five times was he worth above 2.2 WAR with my adjustments. Every other HoMEr has at least seven such seasons.

- Sal Bando is the only other player. I rank him only #20 at third base. He’s behind Ned Williamson, a guy who’s already received a HoME obituary. And he’s a near doppelganger of Heinie Groh, a guy about whom we’re still not sure. Among non-pitchers, he ranks ahead of three hitting HoMErs: Bill Freehan, Roy Campanella, and George Wright on my list. He also doesn’t have the negatives associated with Dunlap or Jennings. He has five years at 5.3+ WAR, three more at 4.4+, and three more at 2.9+. Without him, third base may be our least populated position other than catcher. And it appears that Bando’s sixteen seasons in the bigs are underpopulated in the HoME as well. I’m not 100% certain my vote for Bando is correct, but the fact that no eligible player without extenuating circumstances has led the bigs in non-pitcher WAR over a five-year period makes me think I’m probably doing the right thing.

Miller

Charlie Bennett Goes Saberhagen

The Hall of Miller and Eric is a collaborative process. It has to be. And per our rules, we must select 209 players for induction by the tie we complete our 2013 election. Those same rules tell us that nobody gets inducted without a vote from both of us. Thus, players who get votes from one of us need tremendous consideration from the other. Otherwise we’re going to run into quite a predicament when we get to our last few elections.

Eric has voted for three players – George Wright, Paul Hines, and Charlie Bennett in each of our six elections. And while I haven’t voted for any of them yet, I’ve maintained from the start that George Wright is a very strong candidate who will very likely receive my vote one day. And I’ve recently decided that there’s about a 70% chance I vote for either Paul Hines or center field contemporary Pete Browning at some point. But I’ve never given serious consideration to Eric’s third solo nominee, Charlie Bennett.

Charlie Bennett was a catcher whose career lasted 15 years in the National League (1878, 1880-1893). Unlike many catchers of the period, Bennett was a true backstop, playing 88% of his innings behind the plate. In order to get a better grasp on Bennett and see what Eric’s votes have been all about, I’m going to run the durable catcher through our Saberhagen List to see if anything comes to the surface for me.

Full disclosure, I go into this exercise wanting to vote for Charlie Bennett. Either that or I hope my results tell Eric that he should stop doing so. Let’s see what happens!

1. How many All-Star-type seasons did he have?

One way to measure this is to look at his WAR compared to other NL catchers each year of his career. Since there were never more than eight teams in the NL until his last two seasons, he’d have to lead catchers in WAR or be pretty darn close to have an All-Star type season. For the last two, first or second would be fine.

1878: 7th

1880: 4th

1881: 1st, by a good margin

1882: 1st, by a good margin

1883: 1st, toss-up between him and Buck Ewing

1884: 3rd

1885: 1st

1886: 1st

1887: 3rd

1888: 3rd, very close to the top spot

1889: 8th

1890: 2nd

1891: 5th

1892: 16th

1893: 16th

It seems clear that Bennett played at an All-Star level in 1881, 1882, 1885, and 1886. He certainly could have been called the best catcher in the game in 1883 and 1888 too.

2. How many MVP-type seasons did he have?

For a catcher, this is trickier than for most players. Catcher is a tough position to play today, and it was just brutal 120 years ago. It was the seventh year of Bennett’s career before chest protectors came into use. And it wasn’t until 1891, when Bennett had only three more years to play, that large padded mitts were allowed. So we should be more lenient for Bennett than for some others. We’ll consider all of the times he was in the top-10 in the NL in WAR for position players.

1881: 2nd, trailing Cap Anson by 1.6 WAR

1882: 6th, trailing Dan Brouthers by 1.8 WAR

1883: 3rd, trailing Dan Brouthers by .9 WAR

1885: 5th, trailing Roger Connor by 3.7 WAR

By this measure, we can only consider three seasons. He just wasn’t close to Connor in 1885. For the others, let’s look at DRA so we can get a grasp of Bennett’s contribution behind the plate. He wasn’t a very good catcher in 1881. He was good in 1882, but perhaps not enough to jump past five players. In 1883, however, he was very good. I can see a reasonable case that he was the best player in the game that year.

3. Was he a good enough player that he could continue to play regularly after passing his prime?

There’s lots of gray here. Depending on how one views his prime, the case could be made that he hung on for as many as five or as few as two seasons after that period ended. A more fair measure for Bennett is to say that he had a long and productive career for a 19th century catcher.

4. Are his most comparable players in the HoME?

It’s still pretty early in our process for this question. With the caveat that it’s a sub-optimal measure, there are only three catchers in Bennett’s era within 15 WAR of his 39.1. Buck Ewing has beats him with 47.7, and he’s already in the HoME. Jack Clements has 32.0, and we continue to review his candidacy without either of us voting for him yet. The same can be said of Deacon McGuire and his 31.1 WAR.

But the comparison to Ewing might sell Bennett short some. Ewing caught less than half the time. Bennett, as mentioned above, was behind the plate 88% of the time. And while Clements and McGuire caught a similar number of games to Bennett, neither was as talented with the bat or the glove.

I’m not sure Charlie Bennett has any other truly comparable players in the history of baseball.

5. Does the player’s career meet the HoME’s standards?

I suppose he’d bring the average value of the HoME down, but there are a lot of reasons I don’t care about that.

6. Was he ever the best player in baseball at his position? Or in his league?

When running Jimmy Collins through Saberhagen not long ago, Eric brought forth the idea of looking at a three-year run as a sign of positional dominance. Let’s see how Charlie Bennett fares by this measure.

• 1878¬-1880: 9th

• 1879-1881: 5th

• 1880-1882: 1st

• 1881-1883: 1st

• 1882-1884: 1st

• 1883-1885: 1st (dead heat with Buck Ewing)

• 1884-1886: 1st

• 1885-1887: 1st

• 1886-1888: 3rd (King Kelly and Ewing)

• 1887-1889: 3rd (Ewing and Fred Carroll)

• 1888-1890: 5th

• 1889-1891: 10th

• 1890-1892: 10th

• 1891-1893: 11th

It could be argued that this is pretty compelling stuff. For six consecutive three-year periods, Bennett was the best catcher in baseball. Let’s not get too excited though – there were only seven other starting catchers.

7. Did he ever have a reasonable case for being called the best player in baseball? Or in his league?

From 1881-1883, he notched 13.3 WAR compared 13.8 for Dan Brouthers. Given the difficulty of catching, one could argue that Bennett was the game’s best player for that period. Perhaps one should argue that.

8. Is there any evidence to suggest that the player was significantly better or worse than is suggested by his statistics?

Here we have to bring up his position again. There’s no doubt that squatting, catching, and being bombarded by baseballs took away from his hitting ability.

9. Did he have a positive impact on pennant races and in post-season series?

Through 1885, Bennett played on only mediocre to terrible teams. His Detroit Wolverines were a strong team in 1886, but they lost out to the Chicago White Stockings. In 1887, Wolverines won the NL title and beat the American Association’s St. Louis Browns 10 games to 5 in what was the exhibition equivalent of the World Series. Bennett hit .262/.311/.357 on a team that hit .243/.275/.326. He was fine.

By 1891, Bennett was a member of the Boston Beaneaters, winners of the NL pennant. There was no post season that year. Even if there had been, Bennett’s career was winding down. He wasn’t one of his team’s best players. By the time the Beaneaters won the NL pennant in 1892, Bennett wasn’t a very good player. In the Championship Series against the NL’s second best team, the Cleveland Spiders, Bennett was a back-up who came to the plate just seven times during Boston’s 5-0-1 victory, though he did homer. Boston won again in 1893, Bennett’s final season, but again there was no post-season.

Bennett’s impact on pennant races and post-season series is negligible.

10. Is he the best eligible player at his position not in the HoME?

Maybe. Or maybe it’s the newly eligible Roger Bresnahan. I think I prefer Bennett, though I haven’t yet given it a lot of thought. I’m quite confident Eric prefers Bennett, calling him the second best catcher before Gabby Hartnett.

11. Is he the best eligible candidate not in the HoME?

I don’t think so. Right now, I prefer Monte Ward.

At no point has Eric ranked him the best among those eligible, always ranking George Wright, Paul Hines, or both higher.

Though the 1931 class is generally weak, I believe Home Run Baker, at least, is also a better candidate.

Okay, we’ve now answered all of the questions. And I’m not yet compelled to vote for our man Bennett. But I have three more questions I want to answer first. If I can answer any of these in the affirmative, I might be forced to change my mind.

1. Is his position within his era grossly underrepresented in the HoME?

No, it’s not. We’ve elected a 19th century catcher in Buck Ewing. There would be nothing wrong with having a second, but we certainly don’t need one.

2. Is his era, in general, grossly underrepresented in the HoME?

No, it’s not at all. We have nineteen guys from the 19th century in the HoME right now, which I think is an underrepresentation but not a gross underrepresentation. Should we get another 180 or so players into the HoME without giving that honor to another 19th century guy, there might be a problem. Right now, I’m comfortable with the era’s representation.

3. Is his position, in general, grossly underrepresented in the HoME? No, it’s not at this moment. We’ve elected Buck Ewing from his era and nobody yet from the first quarter of the 20th century. That omission isn’t necessarily a bad thing. However, unless there’s much more love for Roger Bresnahan or Ray Schalk than I’m anticipating, we’re not going to elect another catcher until Mickey Cochrane comes up in 1946 (Gabby Hartnett began his career earlier but ended it later, so he’s not eligible until 1951). While I see no problem today, I think there may be an issue as we move forward.

Based on Eric’s voting record and his stated reason for putting Bennett on his ballot, he’s already noticed this catcher problem. I don’t want to turn a blind eye to it, nor do I want to vote for someone about whom I’m just not certain.

This exercise has not convinced me to vote for Charlie Bennett in 1931. It has, however, moved me to believe there’s a better than 50% chance I’ll be compelled to vote for him at some point. I expect that I’ll continue to consider Bennett for many, many elections.

Miller

RIP, Players Falling Off the 1911 Ballot

After each election Eric and I will agree on a number of players who won’t ever receive our vote for the HoME. To pay tribute to them and to make our next round of voting easier, we’re going to remove them from intellectual consideration, though not actual consideration. They’ll receive a brief write-up in this column along with a little trivia about their careers or lives.

There were 778 players we considered for the HoME as we began. Three elections into our journey, we’ve elected 11 and put to rest 36 others, as you’ll note by looking at our RIP category and reading below. That leaves us with 731 players for our remaining 198 spots in the HoME. In other words, we can elect less than 27.5% of the remaining players we’re considering.

And after each election, I’ll offer the following chart to keep you apprised of our progress.

| Year | Carried Over | New Nominees | Considered This Election | Elected | Obituaries | Continuing to Next Election |

| 1911 | 47 | 20 | 67 | 5 | 9 | 53 |

| 1906 | 33 | 28 | 61 | 3 | 11 | 47 |

| 1901 | first election | 54 | 54 | 3 | 18 | 33 |

Let’s pay tribute to those falling from intellectual consideration, and let the obscure trivia begin.

Nig Cuppy is the only pitcher in National League history to score five runs in a nine inning game. That was more than 3% of his career total and about 14% of the total of the best hitting season of his career. As players like Cuppy die off, so do players who were once Spiders, Perfectos, Beaneaters, and Americans. Sad.

Pink Hawley is a guy without too much of a place in baseball history. Sure, he won 167 games, the same total as Bret Saberhagen. And he lost the same number as Dolf Luque, 179, in half as many seasons. But there’s not really even marginally meaningful trivia related to those facts. I suppose Hawley’s claim to fame is that he’s third on the all-time hit batsmen list.

William Hoy was deaf. And at a time when players like George Cuppy (see above) were given racist nicknames, it should come as no surprise that Dummy Hoy was given the name he was. As the apocryphal story goes, Hoy is credited with the inspiration for umpires using hand signals to show ball and strike calls. Of course, if Bill Klem’s Hall of Fame plaque is to be trusted, that’s not possible. Klem introduced these signals, and he began his career after Hoy ended his. Oh well. One more thing – Hoy trails only Tom Brown on the all-time error list for outfielders.

A google search for Silver King tells me about a refrigeration company, a professional wrestler, a resort, a boiler compound company, a cleaning systems company, and then a baseball player. Charles Frederick King won 45 games in 1888 and totaled 179 in over 2700 innings by the time he was 24. The first sidearm pitcher in the game’s history, he won only 32 more games in his career. Who needs stinkin’ pitch counts?

Through age 30, the most similar player in baseball history to big Dave Orr was Hall of Famer and HoMEr Dan Brouthers. Brouthers went on to come to the plate nearly 3800 more times and establish himself as one of the best players ever. Orr didn’t. He left baseball after suffering a stroke. The man with the 11th best batting average and 14th best Adjusted OPS+ in history played only eight years in the majors and falls from intellectual consideration.

Elected to Cooperstown as a manager, Wilbert Robinson won just one game more than he lost in that capacity. As a player, he owns a seven-hit game. And Robinson once tried to set a world record, I suppose, by catching a baseball dropped from a plane at 525 feet. As some tell it, in a practical joke gone wrong, Casey Stengel convinced the aviatrix, Ruth Law, to replace the baseball with a grapefruit. As grapefruits are wont to do when dropped from 525 feet, it exploded upon impact, and Robinson lost an eye. Perhaps that’s the origin of the expression, “it’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye.”

Germany Smith, if you’re looking for a more recent comparison, was Mark Belanger – outstanding with the glove and hopeless at the plate. In only four of his big league seasons did he contribute as much oWAR as dWAR. And for an even more recent comparison, his 8.4 oWAR for his career is less than Mike Trout contributed last season. Even great defenders made loads of errors in the 19th century. Smith trails only Herman Long and Bill Dahlen in errors all-time at shortstop. Auf wiedersehen, Germany.

Over the first six years of his career, Gus Weyhing was pretty terrific. He won 177 games and lost only 124 over 2600+ innings. Then he turned 26. Old man. Next thing you know, the arm of the man they called Rubber-Winged Gus fell off. Not literally. But he did go 87-108 in his final 1700+ innings. Even rubber has a shelf life. I think they should have called him “Wild Gus”. He’s tenth in career walks, fifth in career wild pitches, and hit more batters than any man in baseball history. In fact, his record of 277 hit batsmen is 26% more than that of runner-up, Chick Fraser.

In 1938 Chief Zimmer received exactly one vote for the Baseball Hall of Fame. For comparison, the top candidate, Pete Alexander, received 212 votes that year. And aside from Zimmer there were forty more men who received exactly one vote. Six of them eventually gained enough support to be elected. Not Zimmer. A fine defender, Zimmer is fourth in stolen bases allowed but second in runners caught stealing by a catcher.

Rest in peace, all. Please visit our Honorees page to see the plaques of those who have made it into the HoME, and check back here after the 1916 election for more obituaries.

Miller

1906 HoME Election Results

Congratulations to our second class of inductees, Cap Anson, Roger Connor, and Dan Brouthers for gaining entrance to the Hall of Miller and Eric on our 1906 ballot. The HoME is now populated with six of the greatest players in the game’s history.

Per our rules, all three had to be named on both ballots for induction. Let’s look to see how we voted.

|

Rank |

Miller | Eric |

|

1 |

Cap Anson | Cap Anson |

|

2 |

Roger Connor | Roger Connor |

|

3 |

Dan Brouthers | Dan Brouthers |

|

4 |

Buck Ewing | |

|

5 |

George Wright | |

|

6 |

King Kelly | |

|

7 |

Paul Hines | |

|

8 |

Ross Barnes | |

|

9 |

Charlie Bennett |

Here’s a brief rationale from each voter for each player.

Miller

Cap Anson: To this point, he’s the best player in baseball history.

Roger Connor: At his best, he was great. When he wasn’t his best, he was still very good. He had a very nice peak and a very nice career. Connor is an easy inductee into the HoME

Dan Brouthers: He might be the best power hitter of the 19th century. And he’s another easy call.

Eric

Cap Anson: Best player we’ve seen so far.

Roger Connor: Second best player we’ve seen so far, by a nose over Brouthers.

Dan Brouthers: Third best player we’ve seen so far.

Buck Ewing: Tremendous defense adding to good offensive profile at tough position.

George Wright: Best player before the NA, probably second best player from 1871-1879, maybe the best depending on how one sees Barnes.

King Kelly: The bad-defense and shorter-career version of Ewing. $10,000 sale reflects his performance and popularity. Strong peak/prime performer, would have been higher but for inability to keep it together after age 33.

Paul Hines: Best centerfielder of the pro-game’s first 15 years. Strong similarity to already-enshrined Deacon White in peak, prime, and career value.

Ross Barnes: Most dominant player of the 1870s by far. Among handful to lead league in WAR 5 times. Was still average after illness/injury that ultimately forced him from game. Probably best 2B before Nap Lajoie/Eddie Collins.

Charlie Bennett: He’s the Carlton Fisk to Buck Ewing’s Johnny Bench in the 1880s. Oddly enough his playing style is kind of like Thurman Munson with an even better glove. Munson is a borderliner, this guy is easily over the line for catchers.

Please visit our Honorees page to see their plaques and to see more information about the HoME and those who have been elected.

Positional Talent Clusters, Part I: Knowing Your ABCs

Cap Anson, Dan Brouthers, and Roger Connor (the ABCs!) played concomitantly from 1880–1896 (17 years). All no-doubt all-time greats. Connor (84) Brouthers (79), and Anson (74) combined for an amazing 237 combined WAR in those 17 years. Are they the best trio of first-base talent in history? [By first base, I mean guys who really were first basemen, not guys who moved there after a while or due to injury. Musial, Perez, Banks, Allen, and Jack Clark aren’t who we’re talking about.]

I’m no databaser, so I eyeballed the career WAR leaderboards to see what trios might compete.

- Gehrig (100), Foxx (68), Terry (54): 222 from 1925 to 1936

- Gehrig (108), Foxx (72), Bottomley (28): 208 from 1925 to 1937

- Bagwell (80), Thomas (67), and Olerud (56): 203 from 1991 to 2005

- Pujols (92), Helton (47), and Thome (38): 177 from 2001–2012

- McGwire (62), Palmeiro (58), and Will Clark (56): 176 from 1986 to 2000

- McCovey (62), Killebrew (61), Cash (52): 175 from 1959 to 1974

- McCovey (62), Killebrew (61), Cepeda (47): 170 from 1959 to 1974

- Helton (62), Thome (56), and Giambi (50): 168 from 1997 to 2012

- McGwire (62), Palmeiro (58), and Fred McGriff (47): 167 from 1986 to 2000

- Bagwell (70), Thomas (52), and Delgado (40): 162 from 1993 to 2005

- Pujols (72), Teixeira (45), Gonzalez (31): 148 from 2004 to 2013

There are probably other groups, or other permutations of these trios that I’ve overlooked in my hasty zip through history, please add any you come up with.

The ABCs dominate their own era in a way no one can even get close to, especially when you see how evenly the performance was distributed among the three of them.

But…the 1880s were an easier time to dominate. Easier than the 1920s. Plus the first Gehrig Group did its work in only 12 years, a significantly higher rate of production than the other threesomes we’ve listed. So we should crown the Twenties Trio as the best cluster.

But…the roaring 1920s was a time of pinball offense, with each league usually having a couple doormat teams among the merely eight in its league, and with zero farm systems to procure and develop talent consistently. Not to mention no relief pitching.

So, there is a reasonable argument that the Bagwell Bunch is the most impressive of the lot: they faced tougher competition—the spread from the best performers to the worst (or standard deviation to our statistically-minded friends), was likely lower than the 1920s and the 1880s. And although offense was way up in the 1990s, those guys face numerous competitive conditions (such as relief pitching) that made out-and-out domination more difficult than in previous eras.

—Eric